A: First of all, where did your dirty mind just go because . . . EW! Secondly, the answer is a stick. A Stick.

These are the kinds of jokes that propel me along at mile 90-something of a 100 mile race. It’s not in the telling, actually, but in the run-up in the miles before: thinking about delivery, planning for when I am going to unleash my childish humor on my pacer, wondering if they will smirk or eye-roll or chortle at my selection of amusements. I thought about this one for nearly an hour before it tumbled out of my mouth in the darkness of the 2nd night here out on this course, 2016’s Hardrock Hundred, while we are both fighting fatigue and potential failure.

So it goes. I paid good money to be at Hardrock this year, to take time away from the day-gig, to hand over money to local businesses and boarding establishments, just so that I could be cold out in the mountains after dark, falling asleep on my feet. If the Stoics lived now, they would surely say, “first world problems.”

So, then, WHY?

Ultrarunning is something you could call selfish. But so, I’d argue, are a lot of things. Things that are hard and personal and that we crave acceptance for are also “selfish”. Things that we like to get recognition for from friends or loved ones or just our community at large. How much different is it to the greater social population when evaluating one person’s accomplishment over another’s? Let’s say you’ve always had a problem with getting through the written word ever since small, but you worked hard for weeks and finally finished Don Quixote? That’s an achievement to be sure. Maybe you spent some sleepless nights worrying about the fate of the characters; perhaps meals were skipped, meetings missed. You suffered to get that book done. But get it done you did. And now, you can deservedly receive some congratulations.

When I think about it, an ultramarathon might not be much different than the non-reader finishing a great novel, smiling in contentment at their book club’s congratulations. Or standing back and admiring the deck you just built with a circle of friends over for a BBQ. Or completing your first (or 10th) knitted sweater and showing it off to the needle club and your Facebook group of knitting maniacs.

Ultramarathons are something that I personally pay (not a tiny amount of) money to enter, spend considerable time researching and crafting training plans. Then I must travel and ultimately do some literal suffering to complete the task. Afterwards my gait is a little stiff, my immune system compromised, and my ankles have taken a trip to third-trimester pregnancy status. Even my skin is sunburnt in odd places like one little strip on the right arm and a band on each calf. But I’ve done something that required time and a bit of discomfort, even if that something has no meaning to everyone on the planet save for myself and other participants. Getting a high-five from a small crowd of them is pretty awesome.

To the world, an ultramarathon is at worst stupid and at best a personal victory that is still mostly inconsequential. But to another ultramarathon runner (or “novel reader”), it is really something.

The Janked Up Knee: 2016’s Hardrock Hundred Preamble

I janked up my knee at Fat Dog 120 last August. In the bad weather, the cold, and the petroleum-jelly clay-mud, my knee started doing strange things at mile 25: random shooting discomfort, instability, and, most disturbingly, outright collapse. Most of these symptoms I had had before, so I knew them well. But that was years ago. It was the sudden appearance that was troubling.

To make that long story tolerable, the knee worsened from run to jog to walk to hobble to DNF at mile 80. The 8 months of treatment afterwards (including a couple of unfortunate months of stalling) made me think that it might have been a good idea to DNF at mile 50 instead of 80, but in the moment it is really hard to know what’s going to happen in the aftermath…. whether that’s a long term injury or a finish (or both).

I don’t always camp, but when I do it’s at 10,800 feet.

After my name was drawn in the Hardrock lottery in December, it got real. I doubled down on actually rehabbing my knee (by then a hamstring/glute problem instead) and pondered the coming summer. By March I was doing some medium length runs. By April, days of 25-30 miles were doable, though still infrequent. By June I’d done a 70-mile 3-day weekend and things felt…. stable. This might actually work.

I never looked at my training mileage to compare it to previous years: it was less and I knew it. BUT, it was likely more than the first time I finished back in 2004. Those days I ran weeks in the 30s with barely a double-weekend in there for fatigue training. And yet I finished, in a not-horrible time. Although, I was 30 and living at 7000′ elevation, both of which were factors. Now I’m 42 and this is a good thing in many regards. My legs have way more experience with 100s and mountainous trails in general. But, I live at 500 feet these days and have learned that with each passing year I both value and need my sleep hours. With the prospect of a 2nd night out at Hardrock, I was leery.

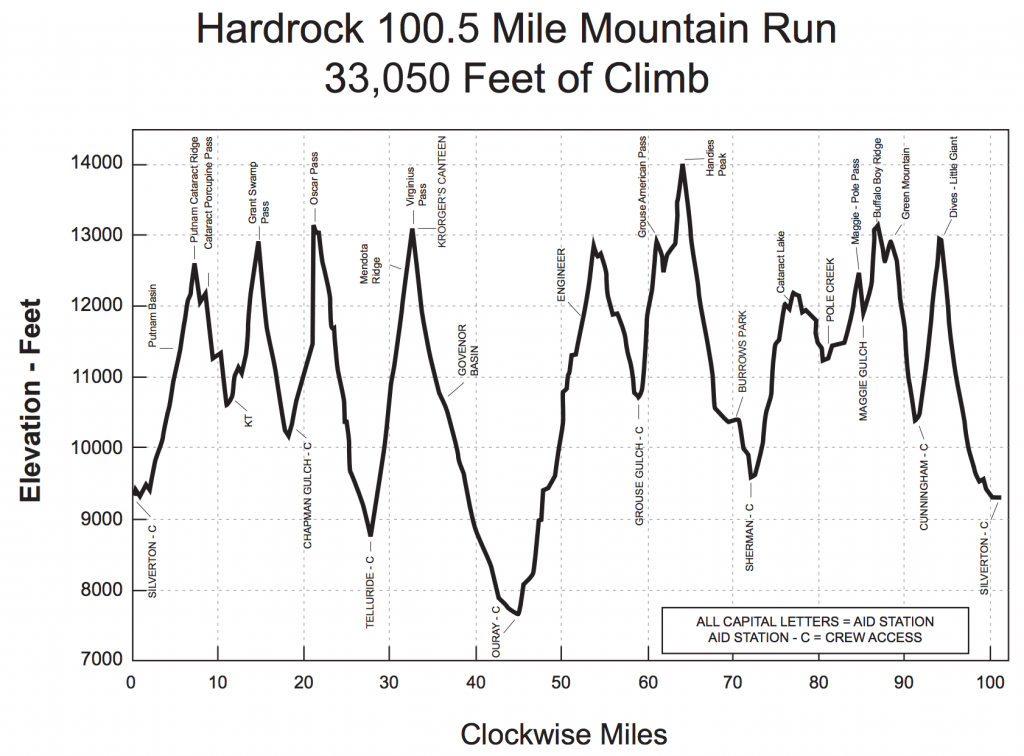

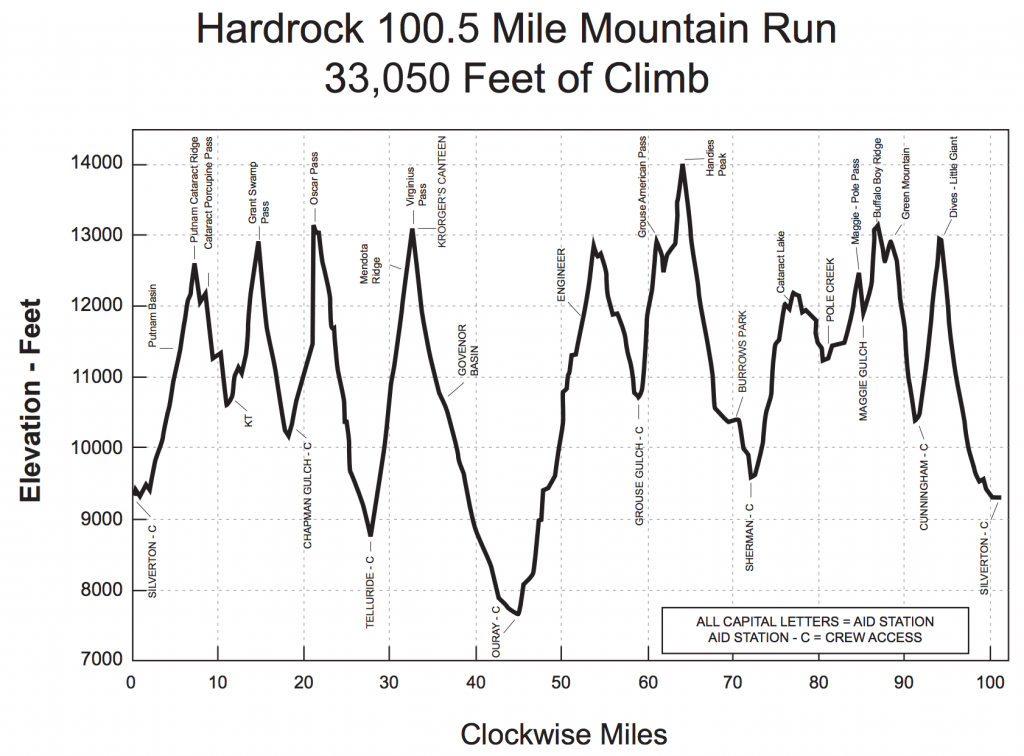

Heat training occupied my late spring, partly for the planned pacing stint at Western States, partly for the altitude-like EPO effects from increased blood plasma volume. A little bit of time training between 6000 and 10,000 feet helped, too, but nothing at all like actually living there. So I set off 10 days early for Silverton with my work projects in tow and began camping at 10,800′ to make some more red blood cells. Because this course averages above 11,000 feet. Yeah:

Hardrock’s Course Profile

My Secret Sauce for Finishing 100s With Gas Left

And then, quickly, race day Friday morning came and we started climbing and I was right back to how things were in 2004. Up to Putnam basin and ridge, slowly like always as I start races. Honestly, I know a lot of folks who find success at 100s by holding back in the beginning so that they have legs and stamina in the middle and final stretches. Previously at Hardrock and at other 100s, my 2nd halves have been barely slower than the 1st half of the race. What’s my secret? Honestly, I think I don’t have a top gear. No top gear means I can’t go out too hard. I just go at what my speed is, and I can do that speed, more or less, until I’m done. If that’s a secret, it’s not a sexy one.

The women of 2016, 16 of us, had decided that we are all going to finish and make history. The word is passed around the field: no woman drops. I like this pressure. Just a little bit of extra push to keep me going. Not that I planned to drop, but who does, really?

By KT (the first aid station), I was exactly on the same pace as 2004. This is neither a good nor bad sign – if much faster I might have been happy but worried. If much slower I would have *definitely* been worried. When chatting with another runner nearby we talk pace and I mention that I of course plan to finish but that 40-44 would be ideal. At this moment I have the thought of a finish right before the end, something like 47:59, and I shudder. That sounds really, really awful. Two full nights out? Dear gawd.

Then the hike up to Grant Swamp pass ensues and the marbles-on-hard-dirt descent. Along the way, Geoff is taking photos and the flies are biting. Luckily the latter isn’t going to last or else I might go out of my mind in the space of a few hours.

Like usual, I’m doing a combination of steady but measured uphills, jogging downhills not as fast as I’d like, passing on the ups, getting passed on the downs. Quite a few folks slip by me on the way down Grant Swamp, where I am as timid as a 90-year-old on crutches. Per Josh Gordon, “That was straight up hazardous!”

Over the next miles I meet a few friends that will spend some back and forth time with me over the next 40 hours: Tina Ure on the way to her 5th finish, Mark Heaphy of a bazillion finishes already, John Horns, Ellen Silva of Santa Fe, Ken Ward, and more. Not all will finish, sadly. But many will do fine. They always do.

Not eating enough: an ultra-only problem

I struggled mightily on a few of the ups, more so than my usual. Enough that it was clear things were awry. Calorie intake in 100s is typically a problem for me, but I don’t always notice it with the ease of other runners who crash on the side of the trail for lack of blood sugar. I’ve seen spectacular bonks in my friends that let them know loud and clear they need more food. With me, however, I just gradually slow down and feel sluggish. Cueing into that should be a key to better race performances, and then not eating the point of gut upset, also a common problem in races. Basically I don’t eat enough, I slow down, I feel slow, I get actually hungry but then I get nauseous because my stomach is empty. It’s a circle.

The slog up Oscar’s at mile 20 was fine. I passed a few folks. After Telluride, however, the climb to Virginius Pass and Kroger’s Canteen was painfully slow and, disturbingly, a little wheezy. But then that climb was over (sketchy final bit done, sketchy snow slide done, sketchy rock/snow slide done, whew) and I was running down the road to Governor’s Basin, and then, Ouray. In the darkness I ran what I could, hoping it was not too early to be doing that. But I made a food mistake while sitting in the warmth of Ouray. Leaving Ouray with eggs in my belly was the wrong approach. Hashbrowns would have been smarter: carbs and a little bit of fat/protein, rather than a boatload of both and no sugar.

Once on the Bear Creek Trail I wanted to stop about every 5 minutes, so I did, breathing hard and then slower and then slower. This is not like me. I typically just grind, grind, grind, passing folks who are stopped for a breather. Now I was the breather girl and folks were passing me. It was embarrassing. Finally Engineer Aid arrived and I realized I need more starch. Potatoes, yes. GU, yes, but yuck. Coke, yes.

Not surprisingly, the rest of the climb to the pass was far better, and the run down into Grouse almost tolerable. Despite being almost an hour behind “schedule”, I felt a bit better and ready to pick up Brenden, my pacer. We warmed up in the tent, pounded down a small amount of food, and set off again into the dawn light. Again I wanted to know if all the women were still in it. You know, just in case I thought I might need to drop and didn’t want to let everyone down. No one had. Off we go. I made it to the Grouse-American pass without too many pauses for recombobulation.

Handies, too, was OK. Slow as I anticipated but not awful. My lungs still felt weird. Not fully “full”. But I was still moving OK, I think. I worried about the descent on the other side, loose and scrappy as it is. But it was far more tolerable than Virginius and that was a relief. We did what I figured was some jogging on the way down to Burrows for more calories. Coffee with hot chocolate? YES. Fried rice (hello, wonderful folks of Burrows!!)? Oh, heck yeah.

For the entire run I took in gels but not enough. They started tasting not so great after only a third of the race, and later on the second day I had to eat each one in 3 stages rather than just knocking each one back in a go. Stay down and digest, digest you little calories! At least they all stayed down. Whew.

The heat on the way to Sherman was noticeable, tolerable. I thanked my hot spring yet again. Then I waited to get to Sherman to ask if any women had dropped. Nope, not yet. Good for all of us! Yet my mind still said, this sucks and maybe you might have to drop, just don’t be the first or only woman. Up the nearly 10 miles to Pole Creek and I saw the aid station in the distance no less than twice before it actually was there in my vision like a mirage. The first time I spotted white and I swore we were almost there. I bet Brenden that the white tent we saw was it.

I lost.

The real Pole Creek consisted of a good literal pit stop, some food, and then we were setting off for Maggie, 4.3 miles that passes like about 43. You’re not yet at that barndoor stage of the race, not with this many miles to go. It’s afternoon and I am falling asleep on my feet, 36 hours into the race. I mention to Brenden that we have at most 12 more hours to get through, which doesn’t at all sound like my idea of a fun weekend.

Nap Time

Suddenly, I wanted to take a nap. The desire was so pervasive and NOW that I think it sounds like an OK tradeoff to just lie down, doze off, and let the race clock run out. This is new. Let’s talk about the past and being 30 and 31, when I first finished this race. How mountain adventures are pretty, well, adventurous. Scree slopes with crazy angles and trails cut into them for a band of runners to traipse over? Awesome. Nighttime storms? Bring it on. Two nights without sleep? Nothing but a few hallucinations and a little surreality.

Oh, but now this body is 42. Sleep is suddenly something of importance for regular functioning. All of those Hardrock “old timers” in their 50s and up who do go the 48 hours without sleep? At this point they are gods. Youthful sleeping habits are surely wasted on the young and the ability to keep standing and moving forward on singletrack trail for two days straight is all of a sudden a fantasy nearly untouchable.

Sleep right at that moment, mid-afternoon on the second day, sounds awesome. So I tell Brenden, “10 minutes. Now.” and set my pack down as a pillow in the low sunlight. For about 3 minutes I am disappointed when sleep does not immediately take over. Then I decide to just get up and keep going and Brenden says, “that was 8”. So I guess there was a little shut-eye, despite my worry. But does it help? Not a lot, and I trudge up the hill.

Into the sunset goes the sleepy runner. Photo by Brenden Goetz

I went deep into my head here. I realized that a lot of what I was feeling is what I was supposed to be feeling, and what I expected to feel. Including the desire to stop. But that didn’t remove any of the feelings or desires, unfortunately. Still, my brain plotted how to be OK with DNFing, even after the last 36 hours of work and toil, and the 36 weeks before that of training, planning, and hoping.

Deciding to DNF

When did I decide that it was going to be the end of my race? I’m not actually sure. I knew that my lungs felt off and not quite up to par. I knew that my legs felt totally fine. But I worried about my speed. Maybe I was just monitoring everything from miles 40 onward, that awful climb up out of Ouray, watching the clock, worrying. By mile 80 I was definitely concerned. And so I gave myself a good talking to, in which I made the very sane assessment that dropping is OK, if that is what needs to happen, if I have junk in my lungs and I cannot climb. I cried just a little at this realization, because I do want to finish. Maybe that’s a good sign, if the pending DNF gets me all sad. Or maybe it’s just a sad thing and not a sign. I think about the races I’ll have to do to re-qualify for this and for Western, the fall training. All of it occupies me for the better part of 5 hours. It seemed perfectly logical. Dropping seemed like all I could do. How could I finish? I could not. Therefore, I should stop. It seemed simple, even if it was difficult to admit.

And then we hit Maggie, finally. Everyone there is happy and that is awesome. Kristina Irvin is here and I ask her how she deals with being sleepy. She says, “sometimes I wake up in the bushes.” Har, and hmm. Not what I was hoping for. Otherwise, I like this aid station because I feel like the climb out of it is not so bad. But I do always forget the climb is two-fold. The first one is OK. The second one is gnarly. I take it slow and feel the lungs doing their icky thing again. I wonder if I am imagining it. Imagining what pulmonary edema feels like without really knowing. Maybe I’m not so bad off. But then I get sad again.

Green Mountain descent right, Divies ascent left, Cunningham center. Photo by Geoff Cordner

For the record, the final descent from Green Mountain is FAR FAR FAR better in the light. Remember that. In the darkness I am reduced to scared tip-toeing down the sliding trail using my poles as legs and generally freaking out nonstop for an hour. In that mess we pass by a huge herd of sheep, bleating in the dark, the yips of their dogs measured and urgent. I thought to turn off our lights and just LOOK through the moonlight to see them, but somehow I never said anything or did it. I regret that. And then I start sliding down the hill again. It ain’t pretty.

Brenden knows what has been going on with me wanting to drop. He is a little resigned about it, too. In retrospect that’s not a great sign, but he doesn’t know me. What is he supposed to do? He is supportive but nudging without being a commander. For the most part, that’s been working. We keep going down, then I get my second dose of brisket for the race. Within a half mile of Cunningham there is someone posted as a trail guardian who warns us about the next stretch and asks how I’m doing. I say that my lungs feel junky and he says that I have “Brisket” and should get down ASAP. Yep, I’m on it, dude.

At the bottom of the trail into Cunningham stood 6 people, silent, with their lights off. It was eerie and a bit somber. Like they were watching our horrible progress and just waiting to see what terrible shape we must be in, what help we might need, what medical attention was required. But all I wanted was someone to listen to my lungs. I plopped down on the chair in the tent and was promptly swaddled in massive blankets, Jabba the Hut style. Two separate med folks listened to my lungs and proclaimed me clean.

Wait, what?

Now that that was resolved and there were 5 and 3/4 hours left on the clock, Cunningham was all business. My friends from Albuquerque set out on their task of getting me out of the aid station and headed up that last crazy mofo climb. But. But… I was done. Quit? Why in the hell would I do that? I had plenty of time (and in fact one of them actually asked me, did I want to take a nap!?) and my lungs were perfect: what’s the problem here? The problem was this: nothing but a whiny ultrarunner who thinks that they can just stop when they want to.

I was to be ferreted out of the tent and back on to the course without even a peep of recognition that here was the place that I was going to drop. Those sentiments were just not heard. When it seemed true that I *was* continuing, I still could not wrap my head around it. I even said out loud, “I just talked myself into being OK with dropping fro the last 4 hours!” To flip that around was excruciating. But according to the folks in that tent, nope, not gonna happen at this aid station. We’re mile 91 and everyone leaves here with a solid chance to kiss that rock. So shove food in my maw they did. Change my socks they did. Instruct me on how to cross the river in backup shoes so that I could put dry shoes on after I crossed and then throw the wet ones over to them. Dang, those guys were genius.

So I guess I’m going…? This is happening. We left at 12:45, a full 4 hours after I left in 2004. I have 5:15 to finish, and I know I’ve done it in 4:50 but that year I felt pretty good. This time, what’s going to happen? I’m going to bust out the poop jokes, that’s what. Brenden brings out his knock-knock joke:

Knock Knock.

Who's there?

Britney Spears.

Britney Spears who?

Knock Knock.

Who's there?

Britney Spears.

Britney Spears who?

Ooops, I did it again.

And we carry on up the hill. That awesomely steep climb I did 4 times in the last 10 days as part of my testing and training. We get up it in 2 hours, the same as in 2004. I am massively relieved, because I know the downhill is ugly. And scary. Some of the singletrack high up has slide areas that make me almost whimper in fear. I make Brenden watch me just in case he needs to stick an arm out. I make it across them all, shaky.

I go back into my head on this downhill, where I ran with my brother 12 years ago. I think about what is happening. What my body and brain have been doing to me. Where does the physiological meet the psychological? In the realm of the psychosomatic, that’s where. In an ultra it explains everything perfectly. Why the lungs didn’t seem to be at full capacity, but there was nothing actually wrong with them when listened under stethoscope. Why the stomach rebelled at the idea of food but then usually would digest what was eaten. Why the arms became sore, why the achilles tightened and moaned, why the ass chafed: because they are SUPPOSED to in a race like this. It’s expected.

In the pre-dawn tinge, Brenden and I still didn’t know how far to the finish. I told him about 2 miles. He says, “it’s 5:15 and I’m worried. Do you think you have another gear?” So I run. Or it feels like running but I’m quite sure it is a 14 minute per mile gimp-jog. The light begins to appear. We bust out above town, bumping down the hill to the ski hut and I see Geoff waiting. We jog. Another runner is coming behind us. I hope it is the doubler guy (Alan Smith), but it is an unexpected treat: Kris Kern, friend and president of Hardrock’s board of directors. He’s had a rough 2 days, too.

We run the last few blocks together before he lets me go ahead—after I tell him he is welcome to the caboose award train tickets with a grin. Knowing we’ll be the last few finishers is dawning on me. The dawn, too: that’s dawning on me. Boy, my brain is fried.

Before this weekend began, before the unraveling mental state, there was that baseline expectation: a finish. It comes.

So That Happened.

And, the surreality. 16 hours after finishing my third Hardrock 100 I have had two “sleeps”, two meals, and one awards ceremony and none of it seems like it actually happened. I’d been planning on Hardrock for a long time, through injury and training and thoughts of a decent time despite any setbacks. And yet, here it had JUST HAPPENED but you could have told me that that was just a dream and Hardrock was still weeks away and I would have accepted that. The brain is a strange animal, in coexistence with my animalish body. And I love that.

Going back to my real life is too fast, even now, a week later. I want a slower on-ramp. I want an easier chute into the hubbub and meetings and deadlines and expectations. Again, to hear the Stoics in my head is therapeutic: